William Tillier with the assistance of Manuel Lubinus

2025.

⚃ 5.4.5.1 Introduction.

⚄ 5.4.5.1.1 Major Features and Cofactors of IBM.

⚄ 5.4.5.1.2 Overview of mitochondria.

⚄ 5.4.5.1.3 Mitochondrial issues as a precursor of IBM; PM-Mito.

⚃ 5.4.5.2 Mitochondrial pathology in IBM.

⚃ 5.4.5.3 Background on Mitochondria.

⚃ 5.4.5.4 The NLRP3 inflammasome, the cGAS/STING pathway and IBM.

⚃ 5.4.5.5 Muscle fiber type distribution and IBM.

⚃ 5.4.5.6 Selected references.

⚃ 5.4.5.7 Extensive references (PDF).

.⚃ 5.4.5.1 Introduction.

⚄ It’s essential not to oversimplify the complex and nuanced role of

mitochondria in skeletal muscle in relation to IBM.

≻ The greatest

representation of mitochondria is found in the heart, brain, and liver, followed by the major skeletal muscles of

the legs (quadriceps) and arms (forearm and finger flexors) and the diaphragm.

≻ Whatever pathological impact is involved in mitochondria in IBM, it is not

a body-wide phenomenon and appears to be secondary to the disease process, not the primary driver.

≻ Portions of this research were done using Perplexity and Gemini 3.

⚄ Mitochondria are a key, functional link in the chain of IBM pathology.

Along with immune activation and protein degradation, these three features define the major pathology observed in

IBM.

≻ It is unclear what the relationship between these three factors

is.

≻ 1. Mitochondria as the “Common

Denominator”

≻≻

Research increasingly positions mitochondria as the intersection point where immune stress meets protein failure.

≻≻≻ Huntley et al., 2019, demonstrated that TDP-43 aggregates

physically “co-exist” with mitochondrial subunits in IBM muscle fibers. More importantly, TDP-43

accumulation appears to disrupt Complex I of the electron transport chain. This suggests a direct mechanistic link:

Protein aggregation → Mitochondrial failure.

≻≻ Connecting to Immune Senescence (T-Cells):

≻≻≻ The specific T-cells that invade IBM muscle (CD8+ TEMRA cells) are

defined by their own mitochondrial dysfunction. They have low mitochondrial mass and rely on glycolysis. This

“metabolic exhaustion” is what drives their senescence and persistence. Thus: Mitochondrial dysfunction

→ Immune senescence.

≻ 2. The “Vicious Cycle” Hypothesis.

≻≻ Since the exact starting point is unknown, researchers often describe the

relationship as a feed-forward loop rather than a linear chain.

≻≻≻ The proposed loop:

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Leaks: Stress (aging or viral) causes mitochondria to release DNA into the cytoplasm.

⏩ Immune Alarm: This “misplaced” DNA triggers the cGAS/STING pathway, alerting the immune system

to a false viral threat. ⏩ Inflammation: This recruits T-cells, which release cytokines (like IFN-γ) that

further stress the muscle mitochondria. ⏩ Protein Failure: The energy deficit from damaged mitochondria

prevents the cell from running its normal “garbage disposal” (autophagy/proteasome), leading to the

accumulation of proteins like TDP-43 and β-amyloid.

≻ 3. Why the “Chicken or Egg” is

Unknown.

≻ The ambiguity exists because we see all three features

simultaneously in patient biopsies:

≻≻ COX-Negative Fibers: These are muscle fibers with dead mitochondria. They

are a hallmark of IBM, but they are also seen in normal aging (but at a lower frequency).

≻≻ Inflammation vs. Degeneration: Some patients have profound inflammation

with little protein aggregation, while others have significant degeneration with mild inflammation. This variability

makes it difficult to say definitively that “A causes B.”

Muscle fibre or muscle cell?

People often get confused when researchers discuss muscle fibres. A muscle fibre is the same as a muscle cell.

⚄ 5.4.5.1.1 Major Features and Cofactors of IBM.

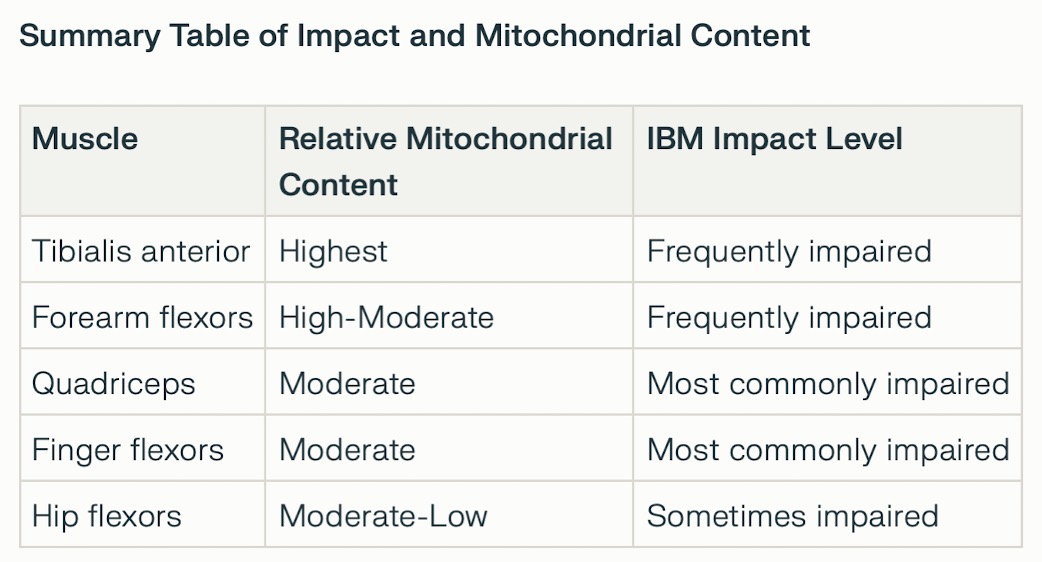

⚅ There does not appear to be a direct correlation between the number of

mitochondria in a muscle and the impact of IBM.

≻ IBM

disproportionately targets voluntary skeletal muscles that combine metabolic activity (high oxidative capacity) and

strength (glycolytic capacity), such as the quadriceps and forearm/finger flexors.

≻ The diaphragm is often impacted (it has a very high mitochondrial density).

≻ Additionally, voluntary skeletal muscles in the throat are often

affected (primarily the cricopharyngeus muscle), causing dysphagia, weakness, and difficulty swallowing.

⚅ In skeletal muscle, the distribution of mitochondria varies by muscle fibre type, with oxidative fibres (type I, found in endurance muscles) containing more mitochondria than glycolytic fibres (type II).

⚅ The relationship between mitochondrial impairment, chronic inflammation, impaired cellular maintenance, and degenerative protein changes is complex and possibly bidirectional, with each factor accelerating disease progression in the impacted muscle groups.

⚅ Degenerative Protein Changes.

≻ In inclusion body myositis, specific

muscle proteins become damaged and misfold, forming clumps within muscle fibres instead of being properly broken

down and recycled by the proteasome and the autophagy-lysosome system.

≻≻ These abnormal aggregates often contain proteins typically linked to

neurodegenerative diseases, such as beta-amyloid and phosphorylated tau, as well as TDP-43, p62/SQSTM1, and various

RNA-binding, ribosomal, and nuclear proteins.

≻ Endoplasmic reticulum

stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative damage further promote protein unfolding and misfolding,

encouraging partially unfolded proteins to stick together and accumulate, especially in aging, chronically inflamed

fibres, where clearance pathways are overwhelmed.

≻≻ These aggregates build

up in and around the “rimmed vacuoles” seen on biopsy, disrupting the normal structure and function of

muscle cells.

≻≻ When researchers first examined muscle cells from patients

under the microscope, they observed these “inclusion bodies” and named the disease inclusion body myositis.

≻≻ Over time, these

aggregates become self-sustaining “crowds” of abnormal proteins that distort cellular architecture and

signalling, and may even spread within a fibre in a prion-like manner, linking early immune-mediated injury to a

progressively degenerative process.

⚅ Impaired Cellular Maintenance.

≻ Impaired cellular maintenance plays a

central role in IBM by reducing muscle fibres’ ability to clear damaged proteins and cellular debris,

especially through malfunctioning pathways such as autophagy and lysosomal degradation.

≻≻ When these cellular housekeeping functions falter, abnormal protein

aggregates, dysfunctional mitochondria, and autophagic vacuoles accumulate within muscle cells, driving chronic

stress responses and ultimately contributing to muscle fibre degeneration.

≻≻ This breakdown in maintenance is compounded by mitochondrial dysfunction,

oxidative stress, and age-related cellular senescence, which further limit the muscle’s ability to repair

itself and maintain normal function.

≻ In everyday terms, IBM muscle

fibres become progressively “cluttered” with biological waste they can no longer clear, so they

gradually lose strength and shrink, leading to slowly progressive weakness and muscle wasting over time.

⚅ Chronic Inflammation.

≻ In inclusion body myositis, persistent

inflammation damages muscle tissue by causing a prolonged, misguided immune response targeting muscle fibres.

≻ Cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes and other immune cells infiltrate the

endomysium and attack even non-necrotic fibres, while regulatory T-cell control is comparatively diminished.

≻ This results in a state of sustained, poorly controlled immune

activity.

≻≻ Shaped partly by interferon-λ and other pro-inflammatory

cytokines, this immune environment fosters cycles of muscle fibre damage, incomplete repair, and progressive

atrophy.

≻≻ It also enhances degenerative changes such as abnormal protein

build-up within fibres.

≻ Although the initial trigger of this immune

response remains unknown, the persistent, treatment-resistant T-cell infiltration and cytokine signalling make

ongoing inflammation a key factor in disease progression, even though it does not alone fully explain IBM or respond

effectively to standard immunosuppressive treatments.

⚅ Mitochondrial Impairment.

≻ Mitochondria in IBM muscle fibres exhibit

significant structural and functional abnormalities, including altered shapes, decreased copy numbers of mtDNA, and

a high occurrence of large mtDNA deletions and duplications compared to age-matched healthy controls.

≻≻ These extensive mutations impair the function of essential mitochondrial

enzymes, such as cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), leading to the formation of “COX-deficient” muscle

fibres that are unable to produce sufficient ATP, thereby increasing their vulnerability to atrophy and shrinkage.

≻≻ This directly contributes to muscle weakness and wasting in IBM.

≻ Overexpression and accumulation of β-amyloid precursor protein

(APP) and its Aβ peptide fragment in IBM muscle are thought to promote oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury,

further disturbing mitochondrial structure, ATP production, and quality-control processes such as fission, fusion,

and mitophagy.

≻≻ In turn, this mitochondrial dysfunction forces muscle

fibres to rely more on less efficient anaerobic energy pathways, contributing to pronounced fatigability and

weakness, while chronically damaged mitochondria release mitochondrial DNA and other danger signals that can

activate inflammasomes and other innate immune sensors, thereby sustaining inflammation.

≻ In everyday terms, excess APP/Aβ “poisons” the mitochondria, so

the muscle runs on a failing energy system that not only weakens the fibres but also keeps the immune system

constantly activated, reinforcing the vicious cycle of degeneration and immune-mediated damage that characterizes

IBM.

⚅ Cofactors contributing to IBM:

⚅⚀ 1. Genetic Predisposition

≻ While IBM is not a classic Mendelian

genetic disorder (it is not passed on from parents to children), the individual’s genetics significantly

influence susceptibility and disease onset.

≻≻ HLA Haplotypes: The strongest genetic risk factor is the

HLA-DRB1*03:01 allele (often part of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype), particularly in Caucasian

populations.

≻≻

HLA-DRB1*03:01 (often referred to as HLA-DR3) is the specific allele that most significantly increases the risk for

sporadic inclusion body myositis (IBM), particularly in Caucasian populations.

≻≻ HLA-DRB1*03:01. Approximately 70-80% of IBM patients carry this allele,

compared to only 20-25% of the general population.

≻≻ This allele is typically part of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype (specifically

the combination of HLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-DQB1*02:01). This haplotype is strongly associated with several autoimmune

diseases.

≻≻ Specific amino acid variances in the HLA-DRB1 peptide-binding groove

(e.g., tyrosine at position 26) facilitate the presentation of specific antigens (possibly autoantigens like cN1A or

viral peptides) to T-cells, driving the autoimmune component.

≻≻ TOMM40 Polymorphisms: Variants in the TOMM40 gene (Translocase of Outer

Mitochondrial Membrane 40), which is in linkage disequilibrium with APOE, act as modifiers.

≻≻ A specific “very long” (VL) poly-T repeat in TOMM40 has been

identified as a protective factor associated with a later age of onset. Conversely, the absence of this protective

variant (shorter repeats) serves as a genetic cofactor for earlier disease development.

≻≻ This connects genetic risk directly to mitochondrial transport efficacy

and cellular aging mechanisms.

≻≻ Mechanism: The risk is driven by specific amino acids in the HLA binding

groove (specifically at positions 26, 11, 13, and 26 of the DRB1 chain), which prefer to bind hydrophobic peptides.

This suggests the disease may be triggered by the presentation of a specific, yet-to-be-identified antigen (viral or self-peptide) to the immune system.

≻≻ DRB4*01:01:01 and DQA1*01:02:01 appear to function as

protective factors.

≻≻ These alleles likely help the immune system distinguish “self”

from “non-self” more effectively or regulate the immune response, preventing the specific autoimmunity

seen in IBM.

≻≻ The highest risk for sporadic inclusion body myositis occurs when a person

has the primary susceptibility allele (HLA-DRB1*03:01:01) AND lacks these protective alleles.

≻≻ Risk Multiplier: Individuals with the high-risk DR3 allele who do not

carry the protective DRB4*01:01:01 or DQA1*01:02:01 alleles have a 14-fold increased

risk of developing IBM compared to the general Caucasian population.

≻≻ Earlier Onset: This specific genetic combination (Presence of Risk +

Absence of Protection) is also associated with a more aggressive disease course, with symptoms appearing on average

5 years earlier than in other patients (Slater et al., 2024).

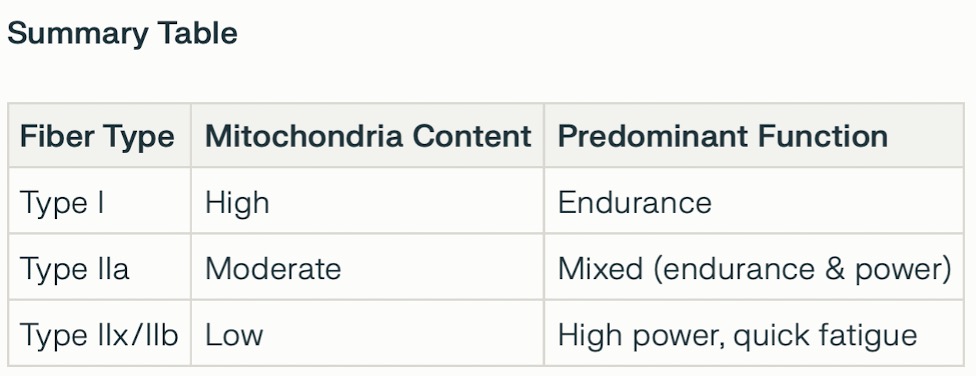

⚅⚀ 2. Aging and “Immunosenescence”

≻ Aging is not merely a passive background but an active cofactor

driving pathogenesis through two distinct mechanisms:

≻≻ T-Cell Senescence: IBM muscles are invaded by highly differentiated,

cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells that have lost CD28 expression (CD28null). These cells are markers of immunosenescence—an

aging-related dysregulation of the immune system often seen in chronic viral infections or advanced age. They are

resistant to apoptosis and chronically secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ), perpetuating muscle damage.

≻≻ Proteostasis Decline: Aging impairs the muscle cell’s ability to

clear misfolded proteins (autophagy defects). This leads to the accumulation of toxic aggregates (e.g., TDP-43, p62,

and β-amyloid) which may physically damage the myofiber and trigger secondary inflammation.

≻ 1. Immunosenescence: The Rise of “Zombie” T-Cells

≻≻ In IBM, the CD8+ T-cells invading muscle are not typical immune

responders; they are biologically aged, or immunosenescent.

≻≻ CD28-null Phenotype: These T-cells have lost the CD28 receptor (a marker

of youth/plasticity) and gained KLRG1 (a senescence marker).

≻≻ High Cytotoxicity: Despite being “senescent,” these cells are

hyper-functional in terms of destruction. They are loaded with cytotoxic granules (perforin/granzyme) and are

resistant to apoptosis (programmed cell death), meaning they accumulate in the muscle and refuse to die or leave.

≻≻ SASP Factor: These senescent T-cells secrete a Senescence-Associated

Secretory Phenotype (SASP), releasing chronic inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) that damage

neighboring muscle fibers and prevent repair.

≻ 2. Muscle Aging as the “Danger Signal” (The cGAS-STING

Bridge)

≻≻ Aging muscle fibers in IBM accumulate damage that mimics viral infection,

tricking the immune system into attacking “self.”

≻≻ Mitochondrial DNA Leakage: As muscle mitochondria age and fail (due to

TOMM40 issues or accumulated deletions), they leak their DNA (mtDNA) into the cytosol.

≻≻ Innate Immune Activation: The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS detects this

leaked mtDNA as “foreign.” It activates the STING pathway, which triggers a potent Type I Interferon

response.

≻≻ The Connection: This mechanism explains why the immune system attacks

degenerating muscle: the aging muscle is essentially screaming “I am infected!” (due to leaked DNA),

recruiting the senescent CD28-null T-cells described above.

≻ 3. Proteostasis and “Inflammaging”

≻≻ Aging impairs the muscle’s autophagy system (the cellular

“trash compactor”), leading to the accumulation of toxic proteins like TDP-43 and p62.

≻≻ Feed-Forward Loop: These aggregates physically stress the cell, further

activating inflammatory pathways (NF-κB) and attracting more immune cells. This local inflammation merges with

systemic “inflammaging” (age-related chronic inflammation), lowering the threshold for autoimmunity in

genetically susceptible individuals (HLA-DR3 carriers).

Summary: The Interaction Model

This interaction explains why immunosuppressants (which target “normal” T-cell activation) often fail in IBM: the disease is driven by senescent pathways and degenerative triggers that standard drugs do not resolve.

⚅⚀ 3. Viral and Environmental Triggers

≻ External factors may act as the initial “hit” that

precipitates disease in genetically susceptible, aging individuals.

≻ At the present time, this is a highly speculative area and no single external trigger has been definitively proven.

≻≻ Retroviral Infection: There is a well-documented general association

between Myositis and retroviruses, specifically HIV and HTLV-1. In these cases, the disease mechanism differs from

typical IBM. In “HIV-IBM,” the HIV virus drives the inflammation (often through T-cell dysregulation

similar to classic sIBM), but these patients are often much younger and may respond differently to treatment (e.g.,

responding to steroids, which classic sIBM does not). In these cases (sometimes termed “IBM-mimics”),

the virus may drive the T-cell senescence and chronic inflammation, even without directly infecting muscle fibers.

≻≻ Medication (Statins): While statin use is a known trigger for anti-HMGCR

myopathy (which acts as a mimic with necrosis), epidemiological studies have also noted a general association

between statin exposure and inflammatory myopathies, likely due to overlapping mechanisms of muscle damage or

diagnostic ambiguity. However, statins are generally considered a distinct trigger for necrotizing myopathy rather

than classic IBM.

⚄ 5.4.5.1.2 Overview of mitochondria.

≻ Mitochondria (singular: mitochondrion) are

structures, a type of organelle, found inside the body’s cells.

≻≻ A single individual has many quadrillions of mitochondria, with the cells

of the muscle, brain and liver having the highest concentrations.

≻≻ One exception; Mature red blood cells do not have a nucleus or

mitochondria.

≻ Mitochondria can move outside of the cell, travel through the blood plasma, and enter other cells.

≻ Mitochondria have a sophisticated system of communication amongst themselves.

≻ When a mitochondrion is stressed, it can signal others to respond for help.

≻ Mitochondria constantly divide [Fission]

and join [Fusion] to maintain a balance of functions within the body and ensure that cells have the energy they

need.

≻≻ Through fusion, mitochondria can share “chemicals”, enzymes

and proteins, and mitochondrial DNA and RNA.

≻ Two mitochondria can also connect using

tiny tunnels (nanotunnels) that act as a bridge between them.

≻≻ They can pass “chemicals” between each other.

≻≻ Mitochondria can exchange signals and adjust enzyme activity to divide the

workload between each other.

≻ Mitochondria can measure the electrical state of other mitochondria and respond if necessary to compensate and maintain a steady overall balance (by fusion or by using tunnels).

≻ Mitochondria synchronize metabolism in the body and respond to cellular stress.

≻ The overall activity of mitochondria is coordinated. For example, during exercise, mitochondria are more active in the muscles and less active in the organs. During rest, mitochondria become more active in various organs, such as the liver, kidneys, and digestive organs.

≻ Mitochondria are controlled by three broad

systems:

≻≻ 1. By the hormonal system in the body (Adrenaline / Noradrenaline,

Glucagon & Cortisol, insulin, and the thyroid hormones);

≻≻ 2. By the nervous system – inputs from the sympathetic nervous

system increases mitochondrial activity in muscles, heart, and brown adipose tissue (for heat production); inputs

from the parasympathetic nervous system promote energy storage and direct resources to organs like the liver,

intestines, and kidneys. Finally, neurotransmitters (acetylcholine, norepinephrine) influence mitochondrial activity

by altering ion fluxes and enzyme activity.

≻≻ 3. By metabolic signals that act within the cell.

≻ The highest numbers of mitochondria are

present in organs demanding the most energy: the heart, brain, liver, and

muscles.

≻≻ The cells of the heart have the highest density of mitochondria in

the body – up to 30 to 40% of cellular volume in the heart is mitochondria. The liver and the brain are also

extremely rich in mitochondria.

≻ Mitochondria are very effective at

producing energy electrochemically in their inner membrane (the cristae).

≻≻ Mitochondria produce energy using this internal membrane – think of

it as a wall. They create an electrical difference, an imbalance – called a gradient, where the electrical

charge on one side of the wall is higher than on the other side.

≻≻ Electrically charged particles move from one side of the membrane to the

other in order to balance the difference.

≻≻ The charges move through

rotating motors (called ATP synthase) in the membrane to create energy.

≻≻ For every ten electrically charged particles (protons) that pass through

one of the motors, the rotating head makes one complete turn, and three new ATP energy molecules are released into

the cell.

≻≻ The motor can spin at over a hundred revolutions per second (Lane, 2015,

p. 73).

≻≻ Extrapolating based on the charge and the size involved this electrical

charge (called the proton-motive force), would be equivalent to a bolt of lightning (Lane, 2015, p. 73).

≻ Mitochondria use oxygen and nutrients from

the food we eat (glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids) to produce energy in the form of a chemical called ATP and

heat.

≻≻ This process is an example of aerobic metabolism.

≻≻ In the process, mitochondria create waste products; water that is

ultimately mostly expelled in urine, sweat or breath, carbon dioxide we breathe out, and an unusual and special

product called oxygen free radicals – Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS).

≻≻≻ You can think of free radicals as being like acid; they are very

damaging to cells and are balanced by antioxidants.

≻≻≻ ROS also have important functions within the cell, thus it’s

important that a balance is maintained: too much ROS is extremely toxic, but too little can also cause problems.

≻ Each Mitochondrion is controlled by two

sets of DNA.

≻≻ The “regular” DNA contained in the nucleus of each cell

contributes to controlling what the mitochondria within the cell do [called nDNA].

≻≻ As well, each mitochondrion contains a very small amount of its own DNA

[mitochondrial DNA (mDNA)] in a circular packet, and each mitochondrion can have multiple packets of mDNA.

≻≻ Considering that each cell can contain thousands of mitochondria, there is

a tremendous amount of mitochondrial DNA in each cell.

≻≻ Mitochondrial DNA are more susceptible to mutations than the regular nDNA

in the cell.

≻≻ Mitochondrial DNA are passed on to children only through the mother,

who’s eggs contain both “regular” DNA and mitochondria (along with their DNA).

≻≻ Sperm contribute “regular” DNA to the children. Sperm contain

mitochondria in their tails, providing energy to move, but these mitochondria are eliminated in fertilization.

≻ Damaged mitochondria often release mitochondrial DNA into the cell, triggering an immune response. As well, some of this mitochondrial DNA can enter the bloodstream and move throughout the body, where it causes additional problems, including widespread inflammation and immune responses.

≻ Normally, old or damaged mitochondria are

flagged and destroyed in a process called mitophagy – a process where defective mitochondria are broken up and

their parts recycled.

≻≻ Mitophagy is an extremely important process, and any

problems with this process can lead to toxic buildups of abnormal mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA

⚄ 5.4.5.1.3 Mitochondrial issues as a precursor of IBM; PM-Mito (Based on Kleefeld et al, 2025).

≻ Researchers see that mitochondrial

dysfunction is a prominent feature of PM-Mito.

≻≻ Over 90% of PM-Mito patients

go on to develop full [late stage] IBM.

≻≻ Thus, PM-Mito appears to be an

early

stage of IBM.

≻ PM-Mito and IBM constitute a spectrum disease.

≻ There are several major abnormalities seen

in the mitochondria of both PM-Mito and IBM.

≻≻ MtDNA copy numbers are significantly reduced [mtDNA depletion], and

multiple large-scale mtDNA deletions are already evident in PM-Mito.

≻≻ The mtDNA defects are maintained throughout all stages of the disease.

≻≻ Ultrastructural abnormalities [seen] include disturbed cristae

architecture and discontinuity of the mitochondrial membranes, possibly allowing a leakage of mitochondrial content

into the body of the cell.

≻≻ In IBM mtDNA leaks from the mitochondria into the body of the cell and

this may be a potential inflammatory trigger.

≻≻ In both PM-Mito and IBM there is activation of the canonical cGAS/STING

pathway – an innate immune response [activation of the canonical cGAS/STING pathway has been linked to T-cell

infiltration, and emerging research suggests it may influence the composition of T-cell subpopulations, including

cells expressing KLRG1].

≻≻ The structure of individual mitochondria become abnormal, some showing a

reduced length to width ratio.

≻≻ Some mitochondria become giant with highly abnormal [densely packed]

cristae [folds in the inner mitochondrial membrane], seen in late stage IBM.

≻≻ Other abnormalities include elevated numbers of COX-negative and

SDH-positive fibers.

≻≻ There is dysregulation of proteins and transcripts linked to the

mitochondrial membranes.

≻≻ Downregulated proteins are seen – 11 of 33 downregulated proteins

were linked to mitochondrial function.

≻≻ Upregulated proteins are seen – the most upregulated protein, with a

6.1-fold upregulation, was a protein located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and involved in various

mitochondrial processes, including heme biosynthesis.

≻≻ Ongoing reduced mtDNA copy numbers point towards an mtDNA maintenance

defect.

≻≻ Multiple mtDNA deletions and depletion may be related to the severe

abnormalities of mitochondrial cristae, where mtDNA replication occurs.

≻ Mitochondrial abnormalities precede tissue remodeling and infiltration by specific T-cell subpopulations (e.g., KLRG1+) characteristic of late IBM.

≻ The initial triggers of mitochondrial dysfunction are unknown.

≻ IBM appears to be a primarily degenerative disease involving mitochondrial dysfunction with peculiar bystander or secondary (auto-) inflammatory features.

≻ In summary, “the role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of IBM is undoubtedly both significant and complex.”

≻ The emerging view implies that abnormal or

damaged mitochondrial release signals (mtDNA and ROS) that activate an immune response through the NLRP3

inflammasome. This activation produces a feedback loop creating a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation

and muscle degeneration.

≻≻≻ mtDNA and ROS are danger-associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs).

≻≻≻ They directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in

muscle fibers and infiltrating immune cells (especially macrophages).

≻≻≻ This view links the degenerative and inflammatory

aspects of IBM – which were once thought to be separate.

≻ A short annotated bibliography on NLRP3 and

IBM. DOWNLOAD PDF.

By Manuel Lubinus.

By Manuel Lubinus.

Why do mitochondria expel mtDNA?

≻The proper functioning of mitochondrial DNA is critical in healthy

mitochondrion.

≻≻ One of the most important questions is: Why do mitochondria expel mtDNA?

≻≻ mtDNA is sensitive to the ratios of different types of nucleotides

– deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs) and ribonucleotides (rNTPs).

≻≻ When rNTPs are present in excess relative to dNTPs, RNA building blocks

are misincorporated into the mtDNA. This imbalance compromises the stability and fidelity of mtDNA replication.

≻≻ This excess causes the mitochondria to expel these unbalanced mtDNAs.

≻≻ This expelled abnormal mtDNA moves into the fluid within the cell (the

cytosol) and as well, it can leave the cell and move throughput the body.

≻≻ This abnormal mtDNA acts as a danger-associated molecular pattern

(DAMP), activating innate immune receptors and triggering an inflammatory response.

≻≻ This is also a key mechanism in the chronic inflammation seen in ageing

– inflammageing.

≻≻ As Conroy, (2025) explained, “When the researchers took a closer

look … they found that the cells contained relatively low levels of DNA building blocks called

deoxyribonucleotides. That short supply forced the mitochondrial DNA to incorporate unusually large numbers of RNA

building blocks while it made copies of itself. This excess of the ‘wrong’ kind of building block

hinders DNA replication … This could explain why the [mitochondria] expelled the mtDNA into the cytosol,

triggering inflammation.”

≻≻ It is not clear if this is a natural process related to normal ageing or

if is a pathological condition.

≻ Imbalanced nucleotide synthesis triggers the release of mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) to the cytosol and an innate immune response through cGAS-STING signalling. … Here we show that

nucleotide imbalance leads to an increased misincorporation of ribonucleotides (rNMPs) into mtDNA during

age-dependent renal inflammation in a mouse model… We demonstrate that increased incorporation of rNTPs into

mtDNA during replication leads to the release of mtDNA fragments from mitochondria and proinflammatory signalling.

… misincorporated rNMPs may cause DNA strand breaks during replication, priming the release of mtDNA

fragments from mitochondria. … our results suggest that an increased rNMP content in mtDNA and mtDNA damage

contribute to immune activation in mitochondrial disorders.

≻≻ Whereas nuclear DNA replication is halted, mtDNA replication continues

in senescent cells. We show that the increased rNTP/dNTP ratio in senescent cells leads to increased

ribonucleotide incorporation into mtDNA, mtDNA-driven cGAS-STING signalling and SASP, highlighting the potentially

far-reaching effects of this mitochondria-dependent inflammatory mechanism in ageing, neurodegenerative diseases

and cancer” (Bahat, et al., 2025).

≻ Bahat, A., Milenkovic, D., Cors, E., Barnett, M., Niftullayev, S., Katsalifis, A., Schwill, M., Kirschner, P., MacVicar, T., Giavalisco, P., Jenninger, L., Clausen, A. R., Paupe, V., Prudent, J., Larsson, N. G., Rogg, M., Schell, C., Muylaert, I., Lekholm, E., … Langer, T. (2025). Ribonucleotide incorporation into mitochondrial DNA drives inflammation. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09541-7

≻ Conroy, G. (2025). Mitochondria expel tainted DNA — spurring age-related inflammation. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-03064-x

≻ Abad et al., 2024: [We see a] self-sustaining loop between inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction/oxidative stress in the [creation] of myositis.

≻ Cantó-Santos et al.,

2023: In mitochondria, several characteristic fibers are displayed which are also seen in primary

mitochondrial diseases and mitochondrial myopathies.

≻≻ [We now see the] systemic impact [throughout the whole body] of this

disease (previously thought to be restricted to muscle) and the relevance of metabolism in IBM (which was thought to

be only minor and secondary).

≻≻ It is still unclear whether these findings could guide future treatment

strategies, but the implication of metabolism and oxidative stress in IBM is now undeniable.

≻≻ Metabolic dysregulation in IBM is present outside the target tissue

(muscle), as seen in altered organic acids in fibroblasts and urine.

≻ D’Amato et al.,

2023: This article reviews several potential treatments and concentrates on the idea of mitochondrial

transplantation (MT) as a potential avenue to explore.

≻≻ Providing healthy

mitochondria may be a more practical solution given the challenges of the presence of multiple and variable mtDNA

mutations.

≻ De Paepe, B.

2019. Based on the cumulating evidence of mitochondrial abnormality as a disease contributor, it is

therefore warranted to regard IBM as a mitochondrial disease, offering a feasible therapeutic target to be developed

for this yet untreatable condition.

≻≻ Muscle of IBM patients seems to display

exaggeration of normal aging-associated degenerative changes, which includes mitochondrial

decline.

≻≻ We can thus conclude that, although mitochondrial alterations are

not the genetic origin, they nonetheless represent an important aspect of IBM disease mechanisms and represents a

druggable and valid therapeutic target.

≻ Hedberg-Oldfors et

al., 2024: Detailed characterization by deep sequencing of mtDNA in muscle samples from 21 IBM patients and

10 age-matched controls was performed after whole genome sequencing with a mean depth of mtDNA coverage of 46,000x.

≻≻ Multiple large mtDNA deletions and duplications were identified in all IBM

and control muscle samples.

≻≻ In general, the IBM muscles demonstrated a

larger number of deletions and duplications with a mean heteroplasmy level of 10% (range 1%-35%) compared to

controls (1%, range 0.2%-3%).

≻≻ There was also a small increase in the

number of somatic single nucleotide variants in IBM muscle.

≻≻ More than 200

rearrangements were recurrent in at least two or more IBM muscles while 26 were found in both IBM and control

muscles.

≻≻ In conclusion, deep sequencing and quantitation of mtDNA variants

revealed that IBM muscles had markedly increased levels of large deletions and duplications, and there were also

indications of increased somatic single nucleotide variants and reduced mtDNA copy numbers compared to age-matched

controls.

≻≻ The distribution and type of variants were similar in IBM muscle

and controls indicating an accelerated aging process in IBM muscle, possibly associated with chronic inflammation.

≻ Huntley et al.,

2024: In this study, we investigated the association between mitochondria and TDP-43 in biopsied skeletal

muscle samples from IBM patients.

≻≻ We found that IBM pathological markers

TDP-43, phosphorylated TDP-43, and p62 all coexisted with intensively stained key subunits of mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation complexes I-V in the same skeletal muscle fibers of patients with IBM.

≻≻ Further immunoblot analysis showed increased levels of TDP-43, truncated

TDP-43, phosphorylated TDP-43, and p62, but decreased levels of key subunits of mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation complexes I and III in IBM patients compared to aged matched control subjects.

≻≻ This is the first demonstration of the close association of TDP-43

accumulation with mitochondria in degenerating muscle fibers in IBM and this association may contribute to the

development of mitochondrial dysfunction and pathological protein aggregates.

≻ Iu et al.,

2024: IBM muscle features major mutations in the DNA of mitochondria.

≻≻ The large-scale mitochondrial DNA deletion, aberrant protein aggregation,

and slowed organelle turnover have provided mechanistic insights into the genesis of impaired mitochondria in IBM.

≻≻ This article reviews the disease hallmarks of IBM, the plausible

contributors of mitochondrial damage in the IBM muscle, and the immunological responses associated with

mitochondrial perturbations.

≻≻ Additionally, the potential application of

mitochondrial-targeted chemicals as a new treatment strategy to IBM is explored and

discussed.

≻≻ The conventional view of mitochondria solely as ATP-producing

powerhouses biased our perception that defective mitochondria in IIM might only result in metabolic deficiency, thus

underestimating its functional outcomes.

≻≻ Recent discoveries that highlight

mitochondrial defects as inducers of immune response via pyroptosis and necroptosis in many different issues have

provided new insights into the pathogenesis of IIM (Figure 1).

≻≻ Hence, it is

imperative to recognize the etiological role of mitochondria and developing novel drugs that improve the

mitochondrial health as a novel treatment strategy for IBM.

≻ Kleefeld et al., 2025: [In summary,] we identified that mitochondrial dysfunction with multiple mtDNA deletions and depletion, disturbed mitochondrial ultrastructure, and defects of the inner mitochondrial membrane are features of PM-Mito and IBM, underlining the concept of an IBM-spectrum disease (IBM-SD). See here.

≻ Kummer et al.,

2023: In the cell culture model of IBM, the NLRP3 inflammasome was significantly activated.

≻≻ It is reasonable to conclude that inflammasomes are a further link between

inflammation and degeneration.

≻≻ The NLRP3 inflammasome is a central component of the interplay between

inflammation and degeneration in IBM muscle and its model systems.

≻≻ Chronic inflammatory stimulus with IL-1ß and IFN-y results in impaired

autophagy, reactive oxygen species and accumulation of ß-amyloid.

≻≻ This leads to an activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and subsequently

higher levels of IL-1ß, and a subsequent vicious cycle leading to more deposition of B-amyloid.

≻ Lauletta et al., 2025. Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a key element informing about disease severity and poor clinical outcomes in non-IBM myositis. It may predict progression to IBM, especially in PM-Mito and NSM, and guide treatment strategies. The presence of mitochondrial pathology appears to significantly increase the risk of developing IBM over time and was associated with treatment refractoriness and worse clinical outcome evaluated based on residual muscle weakness and the level of independence.

≻ Lindgren et al.,

2024: We conclude that COX-deficient fibers in inclusion body myositis are associated with multiple mtDNA

deletions.

≻≻ In IBM patients we found novel and also previously reported

variants in genes of importance for mtDNA maintenance that warrants further studies.

≻ Lubinus:

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Oxidative stress and the release of mitochondrial DNA into the cytoplasm of the cell can

trigger inflammasome activation.

≻≻ This damaged mitochondrial DNA might

provoke an autoimmune response, leading to the production of cN1A antibodies.

≻ Naddaf, Nguyen et al., 2025: The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in IBM, along with altered mitophagy, particularly in males. [Mitophagy removes and recycles damaged mitochondria and regulates the biogenesis of new, fully functional ones preserving healthy mitochondrial functions and activities.] [The inflammasome is part of the innate immune system, responsible for triggering inflammatory responses and cell death.] See here for more information.

≻ Naddaf, Shammas et al., 2024: Investigation of the mitochondria-centered metabolome revealed clinically significant alterations in central carbon metabolism in IBM with major differences between males and females.

≻ Oikawa et al.,

2020: Bioenergetic analysis of IBM patient myoblasts revealed impaired mitochondrial function.

≻≻ Decreased ATP production, reduced mitochondrial size and reduced

mitochondrial dynamics were also observed in IBM myoblasts.

≻≻ Cell vulnerability to oxidative stress also suggested the existence of

mitochondrial dysfunction.

≻≻ Mitochonic acid-5 (MA-5) increased the cellular ATP level, reduced

mitochondrial ROS, and provided protection against IBM myoblast death.

≻ Oldfors et al.,

1995: In this study enzyme histochemical analysis showed that cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-deficient muscle

fibers were present at a frequency ranging from 0.5 to 5% of the muscle fibers in a series of 20 IBM patients.

≻≻ In age-matched controls, only occasional COX-deficient muscle fibers were

present.

≻≻ Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of DNA extracted from

muscle tissue of the IBM patients showed multiple mtDNA deletions.

≻≻ PCR

analysis of isolated, single muscle fibers showed presence of mtDNA with only one type of deletion and deficiency of

wild-type mtDNA in each COX-deficient muscle fiber.

≻≻ This finding was

supported by results from in situ hybridization using different mtDNA probes on consecutive sections.

≻≻ A 5 kb deletion was identified in all 20 IBM patients.

≻≻ DNA sequencing of the breakpoint region showed that this deletion was the

so-called “common deletion.”

≻≻ Most but not all of the

investigated deletion breakpoints were flanked by direct repeats.

≻≻ COX-deficient fibers were more frequent among fibers with positive

immunostaining with antibodies directed toward a regeneration marker, the Leu-19 antigen, than in the entire fiber

population.

≻≻ These results show that COX deficiency in muscle fiber

segments in IBM is associated with deletions of mtDNA.

≻≻ Clonal expansion of

mtDNA with deletions may take place in regenerating muscle fibers following segmental necrosis.

≻ Oldfors et al.,

2006: Mitochondrial changes are frequently encountered in sporadic inclusion-body myositis (s-IBM).

≻≻ Cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-deficient muscle fibers and large-scale

mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) deletions are more frequent in s-IBM than in age-matched controls.

≻≻ COX deficient muscle fibers are due to clonal expansion of mtDNA deletions

and point mutations in segments of muscle fibers.

≻≻ Such segments range from

75 um to more than 1,000 um in length.

≻≻ Clonal expansion of the 4977 bp

“common deletion” is a frequent cause of COX deficient muscle fiber segments, but many other deletions

also occur.

≻≻ The deletion breakpoints cluster in a few regions that are

similar to what is found in human mtDNA deletions in general.

≻≻ Analysis in

s-IBM patients of three nuclear genes associated with multiple mtDNA deletions, POLG1, ANT1 and C10orf2, failed to

demonstrate any mutations.

≻≻ In s-IBM patients with high number of

COX-deficient fibers, the impaired mitochondrial function probably contribute to muscle weakness and wasting.

≻≻ Treatment that has positive effects in mitochondrial myopathies may be

tried also in s-IBM.

≻ Rygiel et al.,

2015: Our findings suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction has a role in IBM progression.

≻≻ A strong correlation between the severity of inflammation, degree of

mitochondrial changes and atrophy implicated existence of a mechanistic link between these three parameters.

≻≻ We propose a role for inflammatory cells in the initiation of

mitochondrial DNA damage, which when accumulated, causes respiratory dysfunction, fibre atrophy and ultimately

degeneration of muscle fibres.

≻ Although it is commonly said that the

function of mitochondria are energy production, in reality, they serve many other functions.

≻≻ 1. ATP Production (Energy

Generation).

≻≻≻ Mitochondria generate adenosine

triphosphate (ATP)

≻≻≻ This is the primary energy

source for most cellular processes.

≻≻ 2. Regulation of Cellular Metabolism.

≻≻ 3. Heat Production.

≻≻ 4. Apoptosis (Programmed Cell Death).

≻≻≻ Mitochondria control apoptotic pathways.

≻≻≻ This is vital for removing damaged or unwanted

cells (e.g. cells infected by a virus).

≻≻ 5. Mitochondria help regulate calcium.

≻≻≻ Cellular signaling

≻≻≻ Muscle contraction

≻≻≻ Neurotransmitter release

≻≻≻ Metabolic enzyme activity

≻≻ 6. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production & Detoxification.

≻≻≻ The electron transport chain of mitochondria

produces ROS as byproducts.

≻≻≻ Mitochondria contain antioxidant enzymes to

neutralize excess ROS and prevent oxidative damage.

≻≻ 7. Mitochondrial DNA and Protein Synthesis.

≻≻≻ Mitochondria have their own DNA (mtDNA) and

ribosomes.

≻≻≻ They produce some of their own proteins essential

for oxidative phosphorylation.

≻≻ 8. Mitochondria participate in various signaling pathways, influencing:

≻≻≻ Cell growth and differentiation

≻≻≻ Inflammation

≻≻≻ Stress responses

⚄ 5.4.5.3.1 Structure: There are five distinct parts to a

mitochondrion:

≻≻ 1. The outer mitochondrial membrane,

≻≻ 2. The intermembrane space (between the two membranes),

≻≻ 3. The inner mitochondrial membrane,

≻≻ 4. The cristae space (formed by foldings of the inner membrane), and

≻≻ 5. The matrix (space within the inner membrane), which is a fluid.

https://www.britannica.com/science/mitochondrion#/media/1/386130/17869

⚄ 5.4.5.3.2 Mitochondria are dynamic:

≻ Mitochondria are primarily found within the cells, however, it is now recognized that some cell types export their mitochondria for delivery to developmentally unrelated cell types, a process called intercellular mitochondria transfer (Borcherding & Brestoff, 2023).

≻ Definitions:

≻≻ Vertical inheritance of mitochondria: mitochondria passed on to daughter

cells during cell division.

≻≻ Horizontal or intercellular transfer of mitochondria: the delivery of

mitochondria from one cell type to another, not through vertical inheritance.

≻≻ Free mitochondria: mitochondria that have been released from a cell but

are not enveloped by an additional membrane structure, such as an extracellular vesicle.

≻≻

Extracellular vesicle-associated mitochondria: mitochondria that have been released from a cell and are contained

within an extracellular vesicle.

≻ Mitochondria constantly change their structure, shape, and distribution within the cell in response to cellular needs and environmental conditions.

≻ Mitochondria undergo continuous fusion, fission, movement, and remodeling.

≻ This dynamic behavior is essential for their roles in energy production, cellular stress response, and cell signaling.

≻ Mitochondrial Fusion is when two

mitochondria combine, forming a single, larger mitochondrion.

≻≻ Fusion

allows mitochondria to mix their contents, which helps dilute any damaged components and optimize function.

≻≻ It also supports mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) repair, as the sharing of mtDNA

and proteins can maintain mitochondrial quality.

≻ Fission is the division of a

single mitochondrion into two smaller mitochondria.

≻≻ This process is

important for mitochondrial distribution across the cell, especially to regions with high energy demands.

≻≻ Fission also facilitates the removal of damaged mitochondria through

mitophagy, a quality control process where dysfunctional mitochondria are degraded.

≻ The balance of fusion and fission helps the

cell adapt to changing conditions.

≻≻ In low-energy situations, mitochondria

may undergo fusion to maintain energy production efficiency, while in times of stress, increased fission can help

isolate damaged mitochondria for degradation.

≻ Mitochondria can move around in

the cell to reach areas where energy demand is highest, such as synapses in neurons or areas of active cell

division.

≻≻ This mobility is crucial for maintaining cellular functions in specialized

cells, like neurons and muscle cells, which have widely distributed regions with varying energy needs.

≻ Remodeling: mitochondria adapt

to cellular signals that reflect the cell’s metabolic state, stress levels, or growth signals.

≻≻ For example: Increased energy demands (e.g., during exercise) prompt

mitochondria to increase ATP production, expand in size, and change in number.

≻≻ Stress signals (e.g., oxidative stress or nutrient deprivation) can

trigger mitochondrial fission and mitophagy to remove damaged mitochondria and minimize cellular damage.

≻ Mitochondria can increase in number

(mitochondrial biogenesis) in response to high energy demands or specific signals (e.g., exercise, caloric

restriction).

≻≻ This ability to multiply allows cells to adjust ATP production as needed.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.3 DNA:

≻ Mitochondria and have their own DNA (mitochondrial DNA – mtDNA – the “mitogenome”).

≻ The cell nucleus also contains some genes encoding for about 1200 proteins involved in mitochondrial structure, membrane, and the repair of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

≻ mtDNA is transcribed and replicated differently than the DNA found in the nucleus – nDNA.

≻ nDNA is inherited from both mother and father – mtDNA and All of a person’s mitochondria are only inherited from the mother [During fertilization, sperm mitochondria are typically destroyed].

≻ Having their own DNA allows mitochondria to reproduce independently within the cell and produce some of their own proteins.

≻ Human mtDNA has a tiny amount of DNA – 37 genes (16,569 base pairs): 13 genes for proteins involved in the electron transport chain and ATP production, 22 for transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and 2 for ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs).

≻ Each mitochondrion can contain multiple

copies of its DNA, and a typical human cell has from hundreds to thousands of mitochondria each containing from 1 to

15 molecules of mtDNA.

≻≻ So if you have 1,000 mitochondria in a cell, and each has 10 copies of

mtDNA, that’s about 10,000 total mtDNA molecules per cell.

≻≻ This means there can be thousands of copies of mtDNA within a single cell.

≻ mtDNA evolves from 10 to 20 times faster than

nDNA and has a less efficient damage repair system compared to nDNA.

≻≻ This makes the probability of mutation much higher in mitochondrial DNA.

≻≻ Mitochondrial disease (MD) is associated with a certain threshold of

mutations in the mtDNA.

≻≻ Common mitochondrial diseases occur in the brain, skeletal muscle, heart,

and eye and can occur at any age.

≻≻ Effective treatment of these diseases is challenging because of the number

and variety of mutations involved.

≻≻ In practice, treatment is focused on relieving symptoms.

≻≻ Damaged mitochondria can release fragments of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

into the cell or into the bloodstream.

≻≻ These mtDNA fragments trigger

immune responses.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.4 The endoplasmic reticulum (ER):

≻ The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a part of a transportation system of the cell, and has many important functions such as protein production and folding.

≻ It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER).

≻ The rough endoplasmic reticulum is dotted with ribosomes, which are tiny, spherical organelles responsible for protein synthesis.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.5 Central Carbon Metabolism:

≻ This term refers to a complex network of enzymatic pathways that convert carbon-containing molecules, such as sugars and other organic compounds, into energy and precursor molecules necessary for cell growth, proliferation, and survival.

≻ Central carbon metabolism ensures that cells can efficiently use carbon sources to meet their energy and growth requirements.

≻ Several key components of central carbon metabolism take place in mitochondria where various chemical pathways produce energy necessary for cellular function.

≻ Central carbon metabolism encompasses glycolysis, the Krebs cycle (the TCA cycle), the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the electron transport chain.

≻ Conventionally, the most important role for mitochondria has been seen as the generation of most of the energy needed to power the cell’s biochemical reactions.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.6 Tricarboxylic acid cycle (TAC): It is

important for us to understand the vital role of mitochondria in producing energy.

Abnormalities in this series of chemical steps have been found in IBM.

≻ Cellular respiration is a multi-step chemical process taking place in the mitochondria through which cells transform food – carbohydrates [sugars], fats, amino acids, and oxygen – into chemical energy that cells can utilize.

≻ The process produces waste products –

carbon dioxide and water, which the body gets rid of when we exhale and urinate.

≻≻ This is called aerobic respiration: glucose + oxygen →

carbon dioxide + water.

≻ The energy produced is stored in a small chemical called adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

≻ START: Glycolysis is the

first step in central carbon metabolism, breaking down glucose into pyruvate.

≻≻ This pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria, where it is converted

into acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A), the starting molecule for the Krebs cycle.

≻≻ Step 1. In the first step of the citric acid cycle, acetyl-CoA joins with

a four-carbon molecule, oxaloacetate, releasing the CoA group and forming a six-carbon molecule called citrate.

≻≻ Step 2. In the second step, citrate is converted into its isomer,

isocitrate. This is actually a two-step process, involving first the removal and then the addition of a water

molecule, which is why the citric acid cycle is sometimes described as having nine steps – rather than the

eight listed here.

≻≻

Step 3. In the third step, isocitrate is oxidized and releases a molecule of carbon dioxide, leaving behind a

five-carbon molecule – α-ketoglutarate. During this step, NAD+ is reduced to form NADH. The enzyme

catalyzing this step, isocitrate dehydrogenase, is important in regulating the speed of the citric acid cycle. NADH

is an important carrier of electrons.

≻≻ Step 4. The fourth step is similar to the third. In this case, it’s

α-ketoglutarate that’ oxidized, reducing NAD+ to NADH and releasing a molecule of carbon dioxide in the

process. The remaining four-carbon molecule picks up Coenzyme A, forming the unstable compound succinyl CoA. The

enzyme catalyzing this step, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, is also important in regulation of the citric acid

cycle.

≻≻ Step 5. In step five, the CoA of succinyl CoA is replaced by a phosphate

group, which is then transferred to ADP to make ATP. The four-carbon molecule produced in

this step is called succinate.

≻≻ Step 6. In step six, succinate is oxidized, forming another four-carbon

molecule called fumarate. In this reaction, two hydrogen atoms – with their electrons – are transferred

to FAD, producing FADH₂. The enzyme that carries out this step is embedded in the inner membrane of the

mitochondrion, so FADH₂ can transfer its electrons directly into the electron transport chain.

≻≻ Step 7. In step seven, water is added to the four-carbon molecule

fumarate, converting it into another four-carbon molecule called malate.

≻≻ Step 8. In the last step of the citric acid cycle, oxaloacetate –

the starting four-carbon compound – is regenerated by oxidation of malate. Another molecule of NAD+ is reduced

to NADH in the process. (Khan Academy)

⚄ 5.4.5.3.7 The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP): An anabolic pathway, responsible for generating ribose 5-phosphate and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH).

≻ The pentose phosphate pathway takes place in the liquid cytoplasm of the cell and produces NADPH.

≻ NADPH is involved in protecting the cell against the toxicity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) among other important roles.

≻ The PPP and the Krebs cycle work together to manage carbon flow, energy production, and biosynthetic needs.

≻ Ribose 5-phosphate is a precursor in the synthesis of nucleotides.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.8 The electron transport chain (ETC): The ETC works hand in hand with the TAC to produce energy.

≻ The ETC is made up of four protein complexes and is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane.

≻ For each turn of the TAC cycle, three

molecules of NADH and one molecule of FADH₂ are produced.

≻≻ These molecules

carry high-energy electrons that are transferred to the ETC.

≻≻ The transfer of electrons creates a force that powers ATP synthase to

produce ATP.

≻≻ This process known as oxidative phosphorylation.

≻≻ The majority of ATP comes from oxidative phosphorylation powered by the

ETC.

≻≻ The ETC also regenerates the oxidized carriers needed to sustain the TCA

cycle.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.9 Mitochondrial Functions:

≻ As outlined above, in addition to supplying the cell’s energy, mitochondria are involved in other important tasks:

≻ Signalling:

Mitochondria play a key role in sending signals throughout the cell that act to protect both the mitochondria and

the cell.

≻≻ Stressed mitochondria transport signalling molecules to the nucleus of the

cell, where they trigger an adaptive cellular response.

≻≻ Mitochondria also communicate information beyond the cell membrane to

coordinate functions across various other cells, tissues and organs.

≻ Integration: Mitochondria integrate various metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, the TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid oxidation.

≻ Creating steroid hormones: Mitochondria are the source of all steroid hormones, including the testosterone, progesterone and estrogens, as well as the stress-induced glucocorticoids that function as endocrine signals to promote stress adaptation.

≻ Stress

regulation: Mitochondria are the TARGET of (and are damaged by) chronic psychological stress.

≻≻ Mitochondria also REGULATE physiology and behavior in response to

psychological stress.

≻≻ Mitochondrial disruptions can impact physiological, metabolic, and

transcriptional responses to psychological stress.

≻ Neuroplasticity and mental

health: Mitochondrial dysfunctions cause impaired neuronal metabolism and can lead to

disturbances in neuronal function, neuroplasticity, and brain circuitry.

≻≻ Mitochondria play a role in regulation of neurotransmitters.

≻≻ Studies support the role of impaired mitochondrial functions in many

psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases, including bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia,

psychosis and anxiety.

≻≻ Mitochondria are involved in neuronal development – synaptogenesis,

synaptic development and plasticity.

≻≻ Impaired function of mitochondria leads to impaired bioenergetics,

decrease of ATP production, impaired calcium homeostasis, increased production of free radicals and oxidative

stress.

≻≻ Monoamine oxidase (MAO), the enzyme responsible for the metabolism of

monoamine neurotransmitters, is found bound to the outer mitochondrial membrane.

≻≻ MAOs are involved in a number of psychiatric and neurological diseases,

(e.g., depression) some of which can be treated with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) which block the action of

MAOs.

≻ Regulating Cellular Metabolism: Mitochondria help control the metabolic pathways that produce or break down various biomolecules.

≻ Calcium Storage: They help regulate intracellular calcium levels, which is important for signaling processes and muscle contractions.

≻ Apoptosis (Programmed Cell Death): Mitochondria release certain proteins that can trigger apoptosis, which is a crucial process for maintaining cellular health and development.

≻ Heat Production: In some specialized cells, mitochondria can generate heat (a process known as thermogenesis) to help maintain body temperature.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.10 Mitophagy: A process that removes and

recycles worn out or damaged mitochondria and regulates the creation of new, healthy ones, preserving healthy

mitochondrial functions and activities.

≻≻ Mitophagy is a vital process for cellular function, and its regulation is

complex and tightly controlled.

≻≻ If mitophagy does not remove defective mitochondria, they can promote

inflammatory signals, which can influence systemic inflammation and contribute to diseases like type 2 diabetes,

neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular disorders.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.11 Reactive oxygen species (ROS): ROS are continually being generated as byproducts of cellular metabolism.

≻ They play key roles in normal in cellular signaling and control several biological processes such as inflammation, proliferation, and cell death.

≻ A total of 2-3% of electrons of the electron

transport chain (ETC) in mitochondria “leak.”

≻≻ Oxygen binds to

the electrons and makes superoxide (an ROS) inside mitochondria.

≻≻ Superoxide then produces many other ROS and causes cell death.

≻≻ Thus, mitochondria are the most significant source of ROS production in

cells.

≻ There is a delicate balance between the

levels of normal ROS production and antioxidant defenses.

≻≻ Healthy cells maintain this balance and the ROS do not cause problems.

≻≻ There is growing evidence that stressed mitochondria release ROS in an

effort to return to normal.

≻ This results in altered gene expression in

the cell through a variety of signaling pathways.

≻≻ In particular, redox-activated proteins appear to be involved in this

communication.

≻≻ All proteins supporting antioxidant reactions are encoded in the nucleus,

not in the mitochondria.

≻≻ So, the communication between mitochondria and the nucleus of the cell is

vital.

≻ Inflammatory mediators are significant

inducers of RS production and are implicated in both the initiation and progression of OS. In turn, ROS serves in

mediating immune responses.

≻≻ Most of the ROS generated during inflammation are extremely toxic and they

may result in significant damage to cells by altering protein functions or generating secondary species like lipid

peroxidation and glucose oxidation products.

≻ In a chronic inflammatory state, excess ROS

not only results in the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasomes but will also block the process of

mitophagy (Khelfi, 2024)

≻≻ Therefore, the damaged mitochondria will persist, producing more ROS, and

continuing the activation of more inflammasomes. Cells containing these altered mitochondria may undergo apoptosis

[cell death], which is dependent on ROS as well.

≻≻ The correlation between chronic inflammation and OS has already been

confirmed in several studies and research focuses on the use of antioxidants as treatment basis for these diseases.

≻≻ See: Naddaf, Nguyen et al., 2025 below.

Khelfi, 2024.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.12 Other sources of ROS:

⚄ 5.4.5.3.13 Oxidative stress (OS): Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of ROS and the cell’s ability to neutralize or detoxify the ROS with antioxidants.

≻ This imbalance causes excessive ROS levels, which can damage cellular components such as DNA, proteins, lipids, and can lead to oxidative stress and mitochondrial disfunction.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.14 The cellular stress response (“cellular stress”): Describes various molecular changes that cells experience when subjected to stressors like extreme temperatures, some viral infections, toxins, and mechanical injury.

≻ Abnormal proteins (misfolded or clumped together) can create ER stress (and thus cellular stress) leading to the UPR.

≻ Abnormal proteins can also trigger oxidative stress.

⚄ 5.4.5.3.15 The unfolded protein response (UPR): The UPR is a cellular stress response related to the endoplasmic reticulum that is activated in response to an accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum.

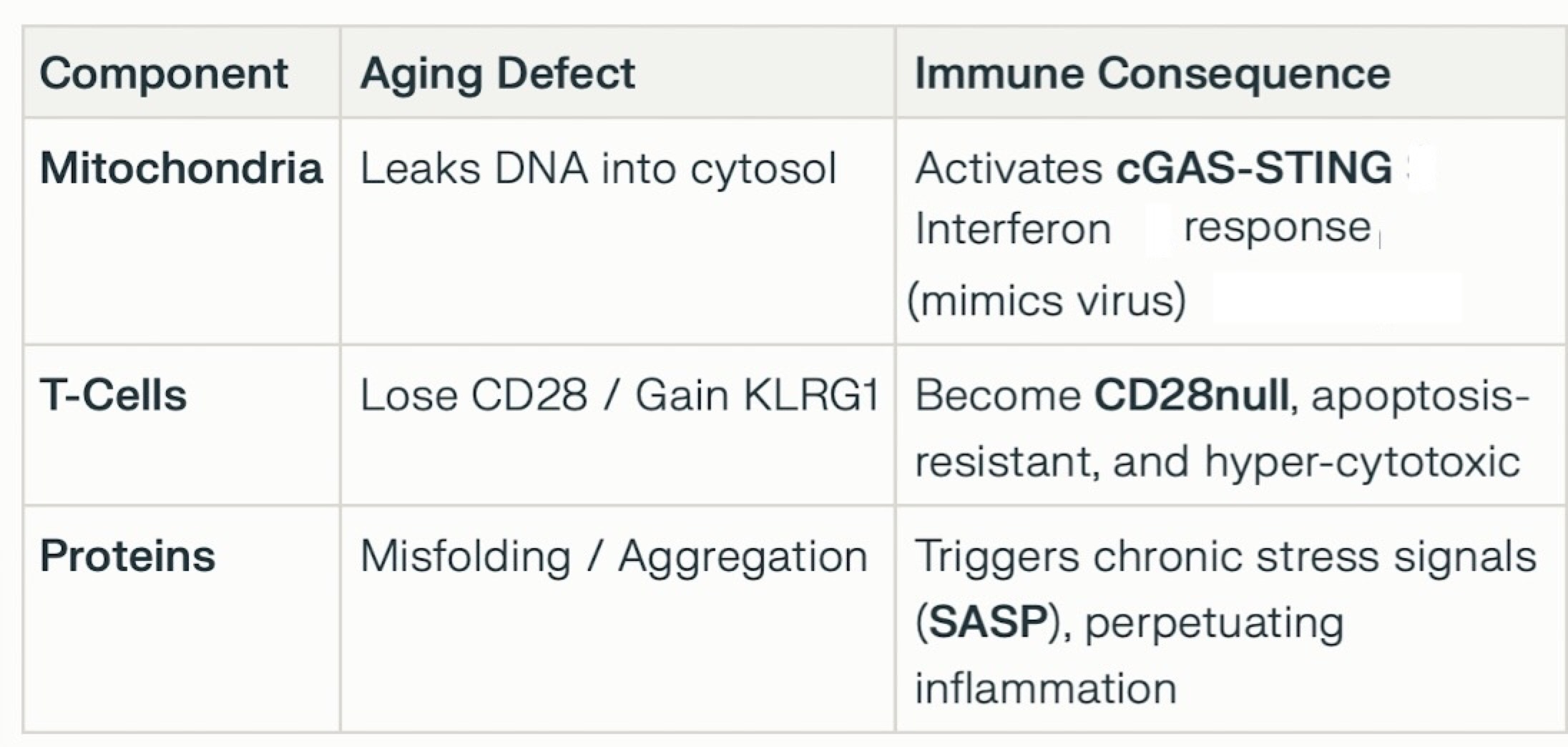

⚄ In inclusion body myositis there is emerging evidence for important

cross-talk between the NLRP3 inflammasome and the cGAS/STING pathway. Both are over-activated, and this contributes

to muscle inflammation and degeneration.

≻ The NLRP3 inflammasome

becomes activated, often in response to mitochondrial dysfunction and the release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and

other cellular danger signals.

≻ Simultaneously, the cGAS/STING

pathway is activated by cytosolic DNA (such as from damaged mitochondria), which further drives the production of

type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines.

≻ Recent studies

underscore significant cross-talk: the activation of one pathway amplifies the activity of

the other, establishing a vicious cycle that perpetuates chronic inflammation and progressive muscle damage in

IBM. This over-activation and interaction of the NLRP3 and cGAS/STING pathways are now viewed as central

mechanisms in IBM pathogenesis, with active investigation into whether therapeutically targeting either or both

pathways might modify disease progression.

⚄ The NLRP3N inflammasome.

≻ NLRP3 is a crucial component of the innate immune system, forming

an inflammasome that drives inflammation through the activation of proinflammatory cytokines and cell death

pathways.

≻ In inclusion body myositis NLRP3 is markedly upregulated

(activated) in muscle tissue, linking chronic inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction to muscle weakness.

≻ The triggers for NLRP3 (over)-activation in IBM are multifactorial

and complex. They are tightly linked to muscle fiber stress and degeneration; specifically mitochondrial

dysfunction, accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates, and heightened inflammatory signaling.

≻≻ These factors interact, fueling a self-perpetuating cycle of chronic

muscle inflammation and degeneration, leading to accumulating muscle weakness and physical disability.

≻ Overactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in IBM muscle leads to

increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, which stimulate muscle cell injury and promote protein

aggregation within muscle fibers.

Inflammasome: a protein complex in the fluid of a cell that regulates immune and inflammatory responses to pathogens.

⚄ NLRP3 activation drives muscle degeneration in inclusion body myositis

through a cascade of chronic inflammation and impaired cellular maintenance. For example, altered mitophagy disrupts

the removal of damaged mitochondria, fueling oxidative stress and further NLRP3 activation in a vicious cycle that

accelerates muscle weakness and atrophy, especially in type 2 muscle fibres.

≻ Summary: The strong association between NLRP3 activation, altered

mitophagy, and IBM severity highlights NLRP3’s significance as both a biomarker and a potential therapeutic

target.

⚄ The cGAS/STING pathway.

≻ Studies show that mitochondrial damage in IBM muscle fibres causes mtDNA

leakage into the cell fluid, where it triggers cGAS/STING signalling and inflammatory cytokine production.

≻ Its activation leads to increased production of inflammatory

cytokines and type I interferons, promoting muscle fibre atrophy and death in IBM.

≻ These mechanisms contribute to the progressive muscle weakness observed in

IBM, highlighting GAS/STING as a potential therapeutic target for intervention.

≻ Summary: The cGAS/STING pathway plays a critical role in inclusion

body myositis by sensing cytosolic DNA released from damaged mitochondria and triggering innate immune

responses.

≻≻ Activation of cGAS/STING via cytosolic mtDNA is thus considered

a key driver of muscle inflammation and degeneration in IBM.

≻≻ Persistent activation creates a toxic environment characterized by

oxidative stress and sustained inflammation, leading to progressive breakdown and loss of muscle fibres typical of

IBM pathology.

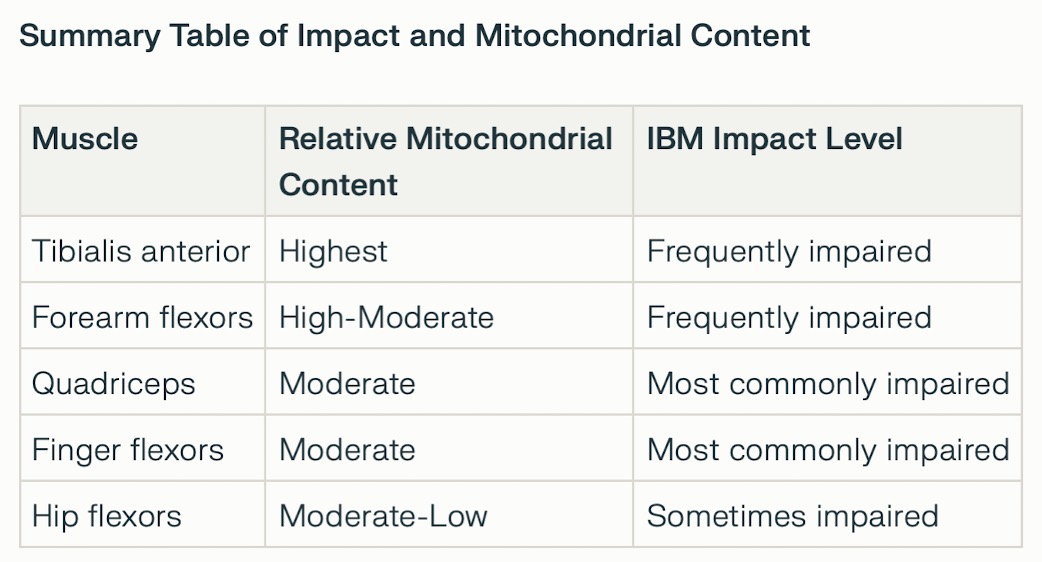

⚄ Skeletal muscle is characterized by two types of fiber, Type 1, slow twitch and Type 2, fast twitch.

Type I (Slow-twitch) fibers

≻

Energy: Primarily use aerobic respiration (oxidative) to produce ATP, requiring oxygen.

≻ Contraction: Slow and deliberate, with a low myosin ATPase

activity.

≻ Fatigue: Highly resistant to fatigue.

≻ Characteristics: Rich in

mitochondria, myoglobin, and capillaries, which makes them appear red.

≻ Best suited for: Endurance activities such as long-distance

running and maintaining posture.

Type II (Fast-twitch) fibers

≻ General: Are faster and generate more force than Type I fibers

but fatigue more quickly.

≻ Subtypes:

≻≻ Type IIa (Fast oxidative): Fast-twitching with a high myosin ATPase

activity. They can use both aerobic respiration and anaerobic glycolysis, giving them an intermediate fatigue

rate.

≻≻ Type IIb/x (Fast glycolytic): Fast-twitching, with a high myosin ATPase

activity. They rely primarily on anaerobic glycolysis for ATP, making them fatigue very quickly.

≻ Characteristics:

≻≻ Type IIa: Appear red due to high myoglobin and

mitochondria content.

≻≻ Type IIb/x: Appear white due to low myoglobin

and mitochondria content.

≻ Best suited for: Short-duration, high-intensity activities like

sprinting and weight-lifting.

⚄ Selective Fiber Vulnerability: IBM muscles exhibit a marked reduction and

selective loss of type 2 (fast-twitch) muscle fiber nuclei and a relative preservation or more diffuse loss of type

1 (slow-twitch) fibers.

≻ The type 2A fibers, in particular, show

pronounced pathology and are closely associated with tissue inflammation, remodeling, and higher levels of

damage-related gene expression.

⚄ Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevalence: Both type 1 and type 2 fibers in IBM can contain cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-deficient segments, indicating respiratory chain dysfunction, but some studies suggest type 2 fibers may be especially prone to atrophy, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell/genomic stress markers when compared to controls or other myopathies.

⚄ Molecular Pathways: Downregulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain genes is seen in affected fibers—type 1 fibers may have lower expression of these genes, but the aggregation of stress-induced and damaged fibers is especially frequent within type 2A populations.

⚄ Functional Consequences: The preferential involvement of type 2 fibers may relate to their higher susceptibility to metabolic stress, inflammation, and impaired repair, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, respiratory chain defects, and fiber atrophy.

⚄ Summary: In IBM, type 2 muscle fibers—particularly type 2A—are disproportionately affected, showing increased mitochondrial damage and stress, loss of myonuclei, and pronounced atrophy, likely due to their metabolic properties and inflammatory microenvironment. These findings highlight that muscle fiber type distribution directly shapes tissue vulnerability to mitochondrial pathology in IBM.

⚄ Oldfors, A., Moslemi, A. R., Jonasson, L., Ohlsson, M., Kollberg, G., &

Lindberg, C. (2006). Mitochondrial abnormalities in inclusion-body myositis. Neurology, 66(1_suppl_1).

https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000192127.63013.8d

≻ Rygiel, K. A., Miller, J., Grady, J. P., Rocha, M. C., Taylor, R.

W., & Turnbull, D. M. (2015). Mitochondrial and inflammatory changes in sporadic inclusion body myositis.

Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, 41(3), 288-303. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12149

≻ Wischnewski, S., Thäwel, T., Ikenaga, C., Kocharyan, A.,

Lerma-Martin, C., Zulji, A., Rausch, H. W., Brenner, D., Thomas, L., Kutza, M., Wick, B., Trobisch, T., Preusse, C.,

Haeussler, M., Leipe, J., Ludolph, A., Rosenbohm, A., Hoke, A., Platten, M., … Schirmer, L. (2024). Cell type

mapping of inflammatory muscle diseases highlights selective myofiber vulnerability in inclusion body myositis.

Nature Aging, 4(7), 969-983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00645-9

≻ Abad, C., Pinal-Fernandez, I., Guillou, C., Bourdenet, G., Drouot, L., Cosette, P., Giannini, M., Debrut, L., Jean, L., Bernard, S., Genty, D., Zoubairi, R., Remy-Jouet, I., Geny, B., Boitard, C., Mammen, A., Meyer, A., & Boyer, O. (2024). IFNλ causes mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in myositis. Nature Communications, 15(1), 5403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49460-1

≻ Al-Hamaly, M. A., Winter, E., & Blackburn, J. S. (2025). The mitochondria as an emerging target of self-renewal in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Biology & Therapy, 26(1), 2460252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2025.2460252

≻ Bahat, A., Milenkovic, D., Cors, E., Barnett, M., Niftullayev, S., Katsalifis, A., Schwill, M., Kirschner, P., MacVicar, T., Giavalisco, P., Jenninger, L., Clausen, A. R., Paupe, V., Prudent, J., Larsson, N. G., Rogg, M., Schell, C., Muylaert, I., Larsson, E., … Langer, T. (2025). Ribonucleotide incorporation into mitochondrial DNA drives inflammation. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09541-7

≻ Blevins, H. M., Xu, Y., Biby, S., & Zhang, S. (2022). The NLRP3 inflammasome pathway: A review of mechanisms and inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14, 879021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.879021

≻ Brady, S., Poulton, J., & Muller, S. (2024). Inclusion body myositis: Correcting impaired mitochondrial and lysosomal autophagy as a potential therapeutic strategy. Autoimmunity Reviews, 23(11), 103644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2024.103644

≻ Cantó-Santos, J., Valls-Roca, L., Tobías, E., Oliva, C., García-García, F. J., Guitart-Mampel, M., Andújar-Sánchez, F., Esteve-Codina, A., Martín-Mur, B., Padrosa, J., Aránega, R., Moreno-Lozano, P. J., Milisenda, J. C., Artuch, R., Grau-Junyent, J. M., & Garrabou, G. (2023). Integrated multi-omics analysis for inferring molecular players in inclusion body myositis. Antioxidants, 12(8), 1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12081639

≻ Conroy, G. (2025). Cells are swapping their mitochondria. What does this mean for our health? Nature, 640(8058), 302-304. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-01064-5

≻ Conroy, G. (2025). Mitochondria expel tainted DNA — spurring age-related inflammation. Nature, d41586-025-03064-x. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-03064-x

≻ Cordero, M. D., Williams, M. R., & Ryffel, B. (2018). AMP-Activated Protein Kinase regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during aging. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 29(1), 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.009

≻ D’Amato, M., Morra, F., Di Meo, I., & Tiranti, V. (2023). Mitochondrial transplantation in mitochondrial medicine: Current challenges and future perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(3), 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24031969

≻ De Paepe, B. (2019). Sporadic inclusion body myositis: An acquired mitochondrial disease with extras. Biomolecules, 9(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9010015

≻ Ding, W., Chen, J., Zhao, L., Wu, S., Chen, X., & Chen, H. (2024). Mitochondrial DNA leakage triggers inflammation in age-related cardiovascular diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 12, 1287447. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2024.1287447

≻ Grazioli, S., & Pugin, J. (2018). Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns: From inflammatory signaling to human diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00832

≻ Hedberg-Oldfors, C., Lindgren, U., Basu, S., Visuttijai, K., Lindberg, C., Falkenberg, M., Larsson Lekholm, E., & Oldfors, A. (2021). Mitochondrial DNA variants in inclusion body myositis characterized by deep sequencing. Brain Pathology, 31(3), e12931. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12931

≻ Hu, M.-M., & Shu, H.-B. (2023). Mitochondrial DNA-triggered innate immune response: Mechanisms and diseases. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 20(12), 1403-1412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-023-01086-x

≻ Huang, Y., Xu, W., & Zhou, R. (2021). NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 18(9), 2114-2127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-021-00740-6

≻ Huntley, M. L., Gao, J., Termsarasab, P., Wang, L., Zeng, S., Thammongkolchai, T., Liu, Y., Cohen, M. L., & Wang, X. (2019). Association between TDP-43 and mitochondria in inclusion body myositis. Laboratory Investigation, 99(7), 1041-1048. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-019-0233-x

≻ Inflammasome. (2024, June 17). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inflammasome

≻ Irazoki, A., Gordaliza-Alaguero, I., Frank, E., Giakoumakis, N. N., Seco, J., Palacín, M., Gumà, A., Sylow, L., Sebastián, D., & Zorzano, A. (2023). Disruption of mitochondrial dynamics triggers muscle inflammation through interorganellar contacts and mitochondrial DNA mislocation. Nature Communications, 14(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35732-1

≻ Iu, E. C. Y., So, H., & Chan, C. B. (2024). Mitochondrial defects in sporadic inclusion body myositis—Causes and consequences. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 12, 1403463. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2024.1403463